I’d been expecting it for a while. The last year of my brother’s life was so difficult for him, and I hated knowing he was suffering. So when the call came Monday morning, I should have felt nothing but relief for him and was surprised by how hard the grief hit. But of course, how could it be otherwise? The older of my two brothers, he’d been in the world as I’ve known it all of my life.

To the world, he was “the Father of ECMO” – the pioneering physician who changed the face of critical care medicine. To me, he was simply “Bobby” – my larger-than-life older brother who would come home from college, sweep me up in his arms, and say “Hi, li’l Bet!,” and despite our often contentious and challenging adult relationship, in my heart, he’s still that tall, adoring older brother, “Bobby.”

Bobby, who was thirteen years older than me, moved out of our house to live in a small cabin he’d built in the backyard when I was two and left for college when I was four, coming home only occasionally for holidays before moving away for good when I was eight, so I never really knew him when I was growing up. I thought of him more as a somewhat distant cousin who would sometimes come to visit -- until the morning in my early 30s when my mother died, when I looked at him I realized our mother died -- that he had just lost his mother, too, my mother, his mother, our mother.

My mother used to tell me we were just alike. I suppose she saw in us the same rebellious streak, the same drive. We were the two doctors of the four of us siblings – he, the medical (i.e., real doctor) and I the PhD (i.e., the Phony Doctor). (I used to long for a time when someone would call the family cabin when he was there and ask for “Dr. Bartlett” and mean me – which I think only happened once out of the many phone calls for “Dr. Bartlett.” 😊. I suppose what I really wanted was his respect.)

But I saw us as opposites in so many ways. We were at odds philosophically. He was a great admirer of Ayn Rand, whom to me was an anathema to all I believed politically and morally. In fact, my first published journal article, "The Contradiction Between Liberalism and Feminism -- Or Why Ayn Rand Is Not the Ultimate Feminist," was in direct response to a conversation he and I had had about her.

For a time, we were also at odds politically. For many years, he was far more likely to support Republicans than I, but Trump brought us together since he hated him as much as I, especially recently with the devastating cuts to the National Institutes of Health that had supported his sixty years of groundbreaking research and for all of the ways that RFK Jr. has been destroying medicine in this country.

He loved to goad me about my feminist beliefs and mocked and belittled my chosen academic field of Women’s Studies, and I would far too often take the bait. He could rile me like no other. But I could anger him as well. I remember vividly the time in London when we were out to dinner with a colleague of his and his wife who were from South Africa, and Bobby said that he’d heard that South Africa was a lovely place. Of course, he was talking about the geography, but my political antennae were up since this was still the era of apartheid, anti-apartheid demonstrations were being held all around the world, and Nelson Mandela was still in prison. My knee jerk reaction was to respond, without thought or tact, “South Africa a lovely place?!!” He refused to talk with me all the way back to our hotel because of how I had embarrassed him and his friends.

Yet, when I needed a second defibrillator surgery and when I received my heart transplant, I wanted him with me, and he came without a moment’s hesitation.

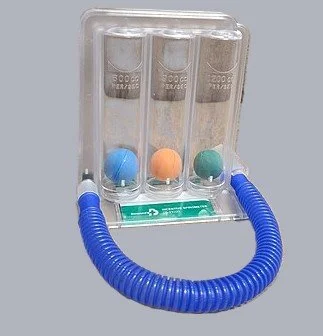

Incentive Spirometer

My brother was brilliant and made enormous contributions to the field of medicine. I was quite proud of him in ways he probably never knew, telling people “my brother invented that” whenever I would see an incentive spirometer in a friend’s hospital room – or my own for that matter, or swelling a bit with pride whenever they mentioned ECMO as a last ditch measure to save a patient’s life on some TV medical drama – they all do.

ECMO – extracorporeal membrane oxygenation – is a life support device that takes over the functions of the heart and lungs, allowing them to rest and heal. He originally developed it to help premature infants survive, since they are born before their lungs were fully developed. I once had the eery experience of visiting his ECMO lab and seeing all these tiny infants lying in incubators hooked up to machines, warm and rosy, but with absolutely no heartbeat or rising of their lungs with the intake of breath. Because of ECMO, Bobby has saved the lives of countless children. He went on to develop uses for ECMO in adult patients, including, ironically, transplant patients. And ECMO became critical in saving the lives of hundreds, perhaps thousands, during the height of the Covid pandemic. When I would call during that time, his wife, Wanda, would tell me he was busy “running the world” over Zoom as hospitals all over the globe were consulting with him about how best to use ECMO with patients with Covid. In another ironic, or hugely coincidental twist, last year the University of Minnesota (my alma mater and the hospital where I received my heart transplant) began using a new mobile ECMO ambulance, the first ever such vehicle used to deliver life-saving care to people suffering cardiac arrests, (I’ve had three), improving survival rates by 30%. (Can you feel my pride swelling as you read this?)

Even though Bobby left home young and moved far away, after several years, he realized that family was incredibly important to him and he moved closer to home.

After my parents died, as the oldest, he became the self-appointed patriarch of the family, which, as the youngest, and the “baby sister,” was more often than not frustrating to me. But I have also been grateful for the ways he took care of certain family matters and made sure the four of us siblings got together from time to time.

He and his wife, Wanda, so often orchestrated family reunions at their home in Ann Arbor or at the family cabin.

With Sir and Lady Bartelot in Stopham, England

He so enjoyed the times when we were all together. He loved to “hold court” at family gatherings and was the keeper of much family lore, including the Bartlett genealogy. When he visited me when I lived in England he, Wanda, and I traveled to the Bartelot estate in Stopham to “meet the family.”

The most reverent I have ever seen him was when he was looking at the stained glass windows of the Bartlett ancestors in the Stopham church sanctuary.

He was devoted to our family, coming to every family wedding, birthday celebration, and even his nephew’s and grand nephew’s college choir and orchestra concerts.

My brother could be incredibly aggravating and infuriating to me and I’ve had my share of grievances over the years, but he was also tremendously loving and generous and magnanimous. He was deeply respected, admired, and beloved by so many. He worked hard and played harder – whether skiing the slopes of Colorado or sailing the seas around the San Juan Islands near Vancouver, or Lake Michigan, or Walloon Lake or playing the upright bass or baritone horn in the Life Sciences Orchestra at the University of Michigan. He lived and loved with such gusto – engaging life the way he did me, sweeping it up in his arms and greeting it with boundless exuberance and love.