“ If only we can overcome cruelty, to human and animal, with love and compassion we shall stand at the threshold of a new era in human moral and spiritual evolution . . . “ - Jane Goodall

A couple weeks ago I had the opportunity to spend a few days in solitude in a place that is my soul’s home. I spent part of my time reflecting on questions to mark the autumnal equinox posed by ecotheologian Mary DeJong. The first question was “What is a desire you carry into the autumn season? What are you seeking?” After much contemplation, the words that came were, “I wish for a change in government – to be rid of Trump and company – for freedom, equality, respect, for the dignity of all, for an end to the suffering in Gaza and the reign of terror of ICE in this country – the horrors of those being abducted and imprisoned – for an end to cruelty. Yes, for an end to cruelty everywhere. Why is this country so cruel? I do not understand cruelty. Where does it come from? Why would anyone want to be cruel? How could anyone even stomach the suffering of another? How does that happen? Yes, I desire an end to cruelty.”

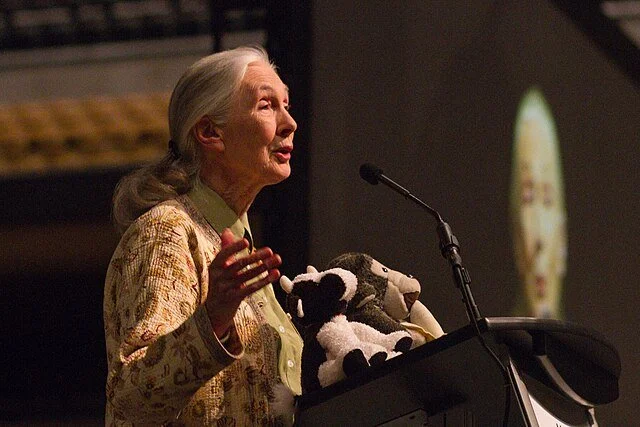

A few days after I wrote those words, on October 1st, scientist, environmentalist, and humanitarian Jane Goodall passed away in her sleep, prompting me to re-read her book, Reason for Hope. There I found her words echoing my own, “To me, cruelty is the worst of human sins. . . “[i] And while she had not set out to study human cruelty, how we become cruel and how we might move beyond our worst impulses, her work with chimpanzees eventually would lead her to this.

The research techniques she used in her study of chimpanzees were controversial. As she herself said, she was “just a girl” with no degree, no training – just a love of animals, curiosity, patience, and empathy. When after months of patient observation she discovered one of the chimps, whom she’d named David Graybeard, using a “tool” – a blade of grass to fish termites out of a hole -- upending hundreds of years of defining humans as the uniquely tool-making animal, her research was discredited.

As she years later recounted to interviewer Krista Tipppett, “I was greeted with scientists who said, ‘Well, you’ve done your study wrong. You shouldn’t have named the chimpanzees. They should’ve had numbers. That’s science. And you can’t talk about personality, mind capable of problem-solving, or emotions, because those are unique to us.’”[ii]

Moreover, the scientists didn’t believe her. Why is it that women are never believed? The only thing that convinced them of the reality of what she had found was the filming of the chimps’ behavior by a man, Hugo van Lawick, who would later become Goodall’s first husband.

When she ultimately pursued her doctorate, Goodall found the research methods used in academia to be utterly wrong. She was being taught to be “coldly” objective, but she knew that it was empathy through which she gained her truest knowledge. “It’s that intuition, that aha moment, which you wouldn’t get if you didn’t have empathy.”[iii] Her work paved the way for feminist critique of the masculinist bias in the scientific method, the development of epistemologies of situated and relational knowledge, and significant scientific discoveries that would not have been made otherwise.[iv]

Goodall continued to live in the rainforest for years, immersing herself in the lives of the chimps. Reading of the deep peace she found in the forest and of her fond relations with the chimps, it was easy to believe that it is our inheritance to be kind and amicable and live peaceably with one another, if only we would restore our relation with the rest of nature. So it was with a sickening feeling that I re-read her accounts of the aggression and brutalities of one group of chimps toward another group. Perhaps the answer to my query about the source of cruelty in humans is simply that the tendency to commit such atrocities is hardwired into our DNA.[v] As she so often stated, humans and chimps share 98.8% of our DNA. She identified the “cultural speciation” she originally found in chimps – the tendency to “other” different groups so as to act toward them in ways that would never be tolerated within our own group — to be “crippling to human moral and spiritual growth,”[vi] and perhaps the greatest enabler of acts of cruelty perpetrated by humans. As philosopher Sam Keen noted, before we can go to war, we must first create the enemy.[vii] The prospect of this tendency to “in-group and out-group” to reside deep in our very being left me despairing for the human condition.

Yet Goodall also found far more prevalent in the chimps the capacity for care, nurturance, mutual assistance and reassurance. She found in chimps’ ability to control their aggressive tendencies and to act toward each other with compassion and love, hope for humans as well -- that we can, in her words, “override our genetic heritage.”[viii] Building on such evidence as the resistance fighters in World War II, the growth of the welfare state, human and animal rights’ movements, and the work of the French philosopher LeCompte DuNuoy, she believed that humans are continuing to evolve morally and spiritually so as to become increasingly less aggressive and more caring and compassionate. She believed in a “flame of pure spirit that is in each and every one of us, that is part of the Creator,”[ix] that if nurtured would enable us to connect with others to create a better world. “If only we can overcome cruelty, to human and animal, with love and compassion we shall stand at the threshold of a new era in human moral and spiritual evolution – and realize, at last, our most unique quality: humanity.”[x] As physicist Brian Swimme, put it, our ultimate destiny is “to become love in human form.”[xi]

Goodall’s most immediate concern was that we might not make it in time. For as intelligent, creative, and loving as humans can be, she thought that we are not so bright. “Bizarre, isn’t it,” she remarked to Tippett, “that the most intellectual creature, surely, that’s ever lived on the planet is destroying its only home.”[xii] She worked passionately to protect the earth, the forests, the animals she loved. Echoing ecofeminist Susan Griffin’s, “We are nature. We are nature seeing nature. We are nature with a concept of nature ...,”[xiii] she sought to impress upon us all that humans are part of nature, here not for dominion and domination, but rather to live in interconnection with all that is. As she said to Tippett, “I could spend hours alone in the rainforest. And that’s where I felt that deep, spiritual connection to the natural world, and also came to understand the interconnectedness of all living things in this tapestry of life where each species, no matter how insignificant, plays a vital role in the whole pattern.“[xiv]

Jane Goodall was a force for good in the world, a saint by her definition of saintliness as “a life lived in the service of humanity, a love of and respect for all living things.”[xv] It’s difficult in these dark times to lose such a light, but her greatest reason for hope was the thousands of young people continuing her work in the world, bright lights all. Her message, repeated often, from her Reason for Hope, written over twenty-five years ago, to her “Famous Last Words” documentary released after her death, was that “each one of us matters, each one of us has a role to play, . . . that multiplied a billion times, even small actions will make for great change, . . . that we have to do everything in our power to make the world a better place, . . . and above all, don’t give up; . . . never lose hope.”[xvi]

Sources

Goodall, Jane. “Famous Last Words.” Netflix. March 2025.

Goodall, Jane with Krista Tippett. “On Being.” Podcast. August 6, 2020.

Goodall, Jane, with Phillip Berman. Reason for Hope: A Spiritual Journey. New York: Warner Books, 1999.

Griffin, Susan. Woman and Nature: The Roaring Inside Her. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

Keen, Sam. “Faces of the Enemy.” Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). 1987.

Swimme, Brian. The Universe Is a Green Dragon: A Cosmic Creation Story. Santa Fe: Bear & Company Books, 1985.

[i] Goodall, Reason for Hope, 225.

[ii] Goodall with Krista Tippett, “On Being.”

[iii] Ibid. I found Goodall’s emphasis on empathy to be particularly moving and profound in this moment when those on the far right are ridiculing empathy as “weak.”

[iv] For example, developmental biologist Barbara McClintock credited her research process of having “a feeling for the organism”—a relational approach – to her Nobel Prize-winning discoveries about genetic transposition.

[v] However, she did believe that only humans had the capacity for true evil. She put it this way to Krista Tippett, “A chimpanzee will kill, but it’s a spur of the moment. It’s an emotion. It’s an emotional response to a situation, whereas we can sit down, far away from an intended victim, and in cold blood plan out the most brutal forms of torture. That’s the difference. And that’s our intellect that has enabled us to think in those terms“ (“On Being”).

[vi] Goodall, Reason for Hope, 133.

[vii] Sam Keen, “Faces of the Enemy.” Sadly, Sam Keen also died this year.

[viii] Goodall, Reason for Hope, 144.

[ix] Ibid., 199.

[x] Ibid., 227.

[xi] Swimme, The Universe Is a Green Dragon, 44

[xii] “On Being.”

[xiii] Griffin, Woman and Nature, 226.

[xiv] “On Being.”

[xv] Goodall, Reason for Hope, 202.

[xvi] Goodall, “Famous Last Words,” Netflix. March 2025, released October 2, 2025.

* Photo credit, Mark Schierbecker, Wikimedia Commons.