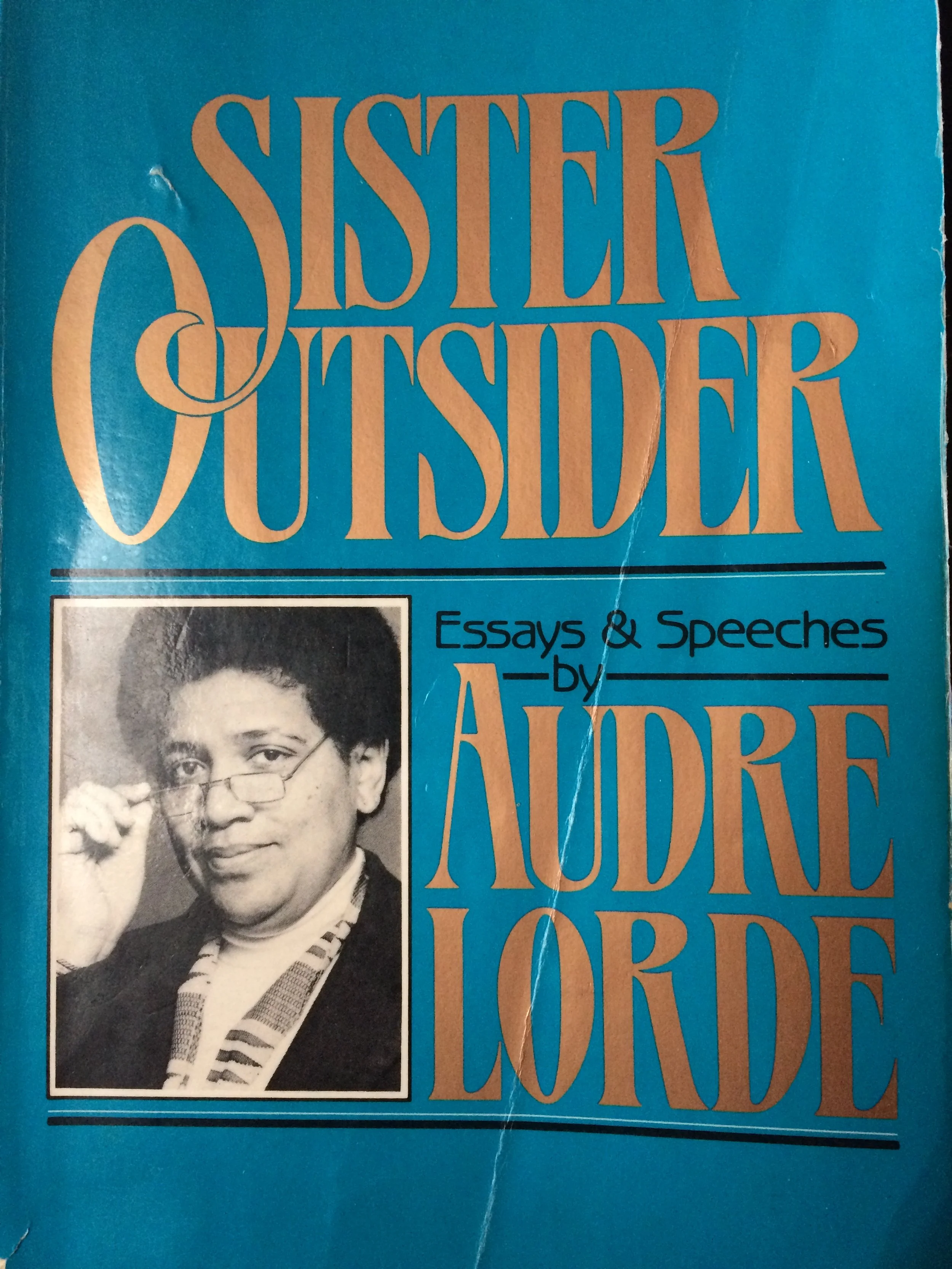

Certain books have changed me in deep and profound ways, shocked me into recognition, helped me see aspects of myself or the world I had not previously seen, brought unconscious truths into conscious action. They are the ones where I’ve starred passages, underlined multiple times, or simply written “Yes!” in the margins; the ones I return to again and again for guidance and inspiration. Among these, probably none is more my lodestar than Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider, and among the fifteen essays, none more than “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.”

I can imagine all the ways this piece might be misunderstood by those who only read the title. “Erotic” and “power” in the common usage have different meanings than those intended by Lorde. “Erotic” has for the most part been reduced to a narrow understanding of sexuality, and is often confused with the pornographic. “Power” is generally understood as meaning “power over,” dominance, conquest, and control. What Lorde intends is something far different.

Lorde understands “erotic” through its root word, eros, “the personification of love in all its aspects” (55). It is the lifeforce giving rise to our creative endeavors – a depth of feeling that enlivens us, the source of our truest knowledge. By power she means a force arising from within, from love, from joy – the power to know, to create, to act, to affirm. Just reading her words, I can sense it rising up in me.

Yet, too often, as Lorde says, “We have been raised to fear the yes within ourselves” (57). We are taught that our passions, longings, and desires are inappropriate, impractical, unnatural, or simply wrong. Living lives shaped by others’ molds, we live “outside ourselves . . . away from those erotic guides.” Others’ expectations, rules, or beliefs; fears of what others will think; a need to fit in; a desire not to discomfit too often determine our words, our actions, our life choices. How many have I listened to over the years whose dreams and aspirations collided with their parents’ or peers’ expectations? How many denied their sexual orientation or their gender expression? How many rejected their very beliefs out of fear of being labeled a heretic, a witch? How many of us silence our questions, bury our gifts, put aside our passions? I certainly have.

But living “from within outward, in touch with the power of the erotic within ourselves, and allowing that power to inform and illuminate our actions . . .” (58), calls us to authentic existence. Our words, choices, and actions in the world align with our sense of self, with our deepest knowings and truths. In responding to our erotic knowledge, we become “responsible to ourselves in the deepest sense” (58). Guided by erotic knowledge, I feel grounded and centered. I know that my actions in the world are my truth.

So often students would ask me how to discern which voices are external and which are internal. It is a studied practice. We are so habituated to living by external directives, it takes time and deliberate attention to listen to the voice within. We can pay attention to those places in our bodies where our actions originate. Are they merely surface-level motions, straight-jacketed, breathless, numb, flat? Or do they emanate from a calm, centered, strong, clear, grounded, energized place in our core?

Perhaps our clearest guide is enjoyment, and by this, I mean not its facile equation with pleasure and amusement, but rather something much deeper. En-joy-ment -- “en,” meaning “to cause to be;” “ment,” meaning “in the state of;” the erotic causes us to be in the state of joy. As Lorde so eloquently expressed, it is the body’s “hearkening to its deepest rhythms . . .whether it is dancing, building a bookcase, writing a poem, examining an idea” (56-57). What brings you joy? Following its lead may be as momentous as the choice of a vocation, a partner, a home, or as quotidian and fleeting as the sunrise or a savored bite of freshly baked bread.

At some point in my nearly forty-year journey with this piece, I wrote in the margin, “to live in touch with the spirit.” Indeed, this depth of joy and knowing are my truest spiritual guides. In my work now as a spiritual companion, Lorde’s piece is the one I most often recommend to those whom I companion to inspire them to find their own spiritual center. My task as a spiritual companion, a teacher, a parent, a writer, a friend, is not to direct, nor dictate, nor fill others with my thoughts and beliefs, but rather to facilitate their listening to their own true centers, whatever these might be, to affirm and honor their unique being in the world. In this I am reminded of another of Lorde’s essays, “Man Child,” where she writes: “The strongest lesson I can teach my son is . . . how to be who he wishes to be for himself. . . and this means to move to that voice from within himself, rather than to those . . .voices from outside, pressuring him to be what the world wants him to be” (77). She recognized this is no small task.

The erotic is a demanding measure by which to live our lives. “Our erotic knowledge empowers us, becomes a lens through which we scrutinize all aspects of our existence. It is a grave responsibility . . . “ (57), but one that, “in honor and self-respect we can require no less of ourselves” (54). On first reading, these words stopped me in my tracks. To treat others with honor and respect was a grounding principle of my life ethic. What would it mean to extend these to myself? To paraphrase Lorde, what would it mean to demand that my life pursuits feel in accordance with that joy which I knew myself to be capable of? Thus began a process of examining my work, my relationships, my pursuits, the places where my time and energies were squandered, the ways I had given myself away -- whether to meet others’ expectations, or obligation, or simply habit, believing that I was making my life easier on some levels. But it was a false sense of ease. True ease in my bodymindspirit, I now know, comes in living in alignment with this erotic guide.

As I’ve written this, I’ve struggled with whether living true to one’s erotic knowledge is a luxury afforded only by a position of privilege. What of those silenced or trapped by poverty, racism, illness, violence, imprisonment? It is true that I have far more autonomy than most, but it seems a shirking of responsibility, not to live true to that erotic guide. Every true word spoken, every empowered act against tyranny, is an act against oppression that extends beyond our individual lives, creating more possibility for all. Lorde’s words echo in my mind, that true knowledge, and the poetry in which it finds expression, “is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change. . . ” (37).

It is the erotic that “gives us the energy to pursue genuine change in the world” (59). I’ve wondered often about Lorde’s statement, “Women so empowered are dangerous” (55). Dangerous to whom? To what? Governments? Corporations? Religious institutions? To what would we no longer submit? conform? accept without question or rebellion? How might families be different, or places of healing or of learning, structures of economy and time, if designed to fit the needs of people rather than patriarchal institutions? What if the endangered species is patriarchy itself? Imagine that instead of rejecting that yes, we embraced it . . . and the world changed. “In honor and self-respect, we can require no less.”

Poster in my office - from Syracuse Cultural Workers

Notes

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde. Trumansberg, NY: Crossing, 1984.