It is the season of emergence. As I write this, the first dragonflies are appearing, emerging from their crusty nymph shells, eyes bulging, wings unfurling, catching the breeze, and rising up into the air. They are not the only insects emerging – the mosquitoes and midges have come before, preparing a feast for them – but they are among the loveliest. Watching the slow process of the dragonfly emerge and wait for its wings to dry and take flight is truly miraculous, and one I never tire of should I happen to be blessed with observing it. Moths and butterflies are also emerging from their cocoons and coming into flight. As are baby birds breaking out of their shells and after frenzied feeding also rise up into the air.

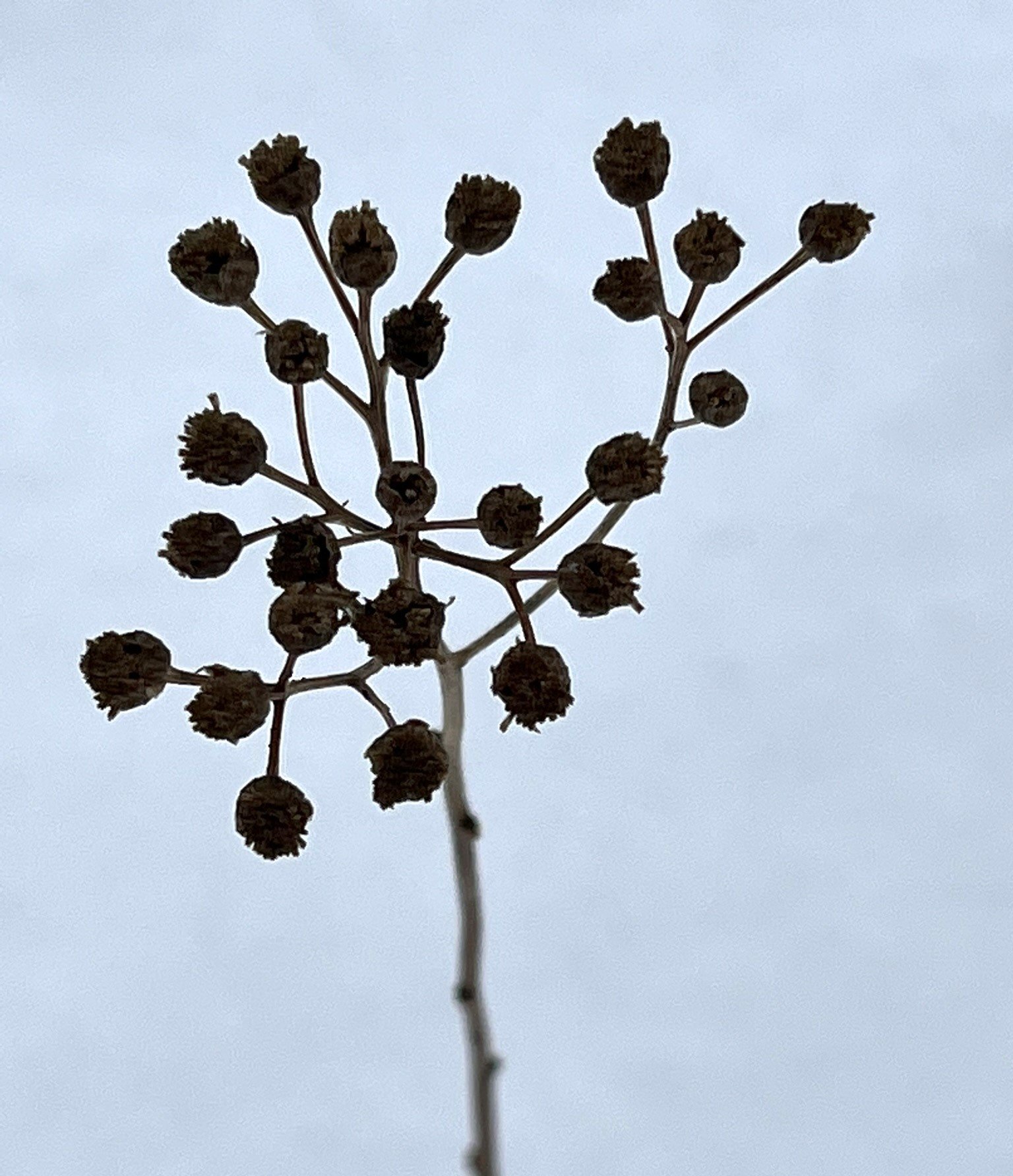

Since I walk the same trail nearly every day, I am keenly aware of new forest life as it emerges, seemingly from nowhere – the ferns, the grasses, the spring green tips of evergreens, but particularly each different flower, whether a flowering bush or the wildflowers that adorn the forest floor. They astonish and delight. It seems every day a different one appears. Their lives are evanescent, usually blooming no longer than a week, maybe two, before beginning their task of creating fruit and seeds for the next generation. But in that brief span of time, they call me to attention, to presence, to gratitude for their loveliness.

The first to appear are the merry marsh marigolds – bright yellow harbingers of spring, they beckon us to emerge from our winter caves to frolic in the woods. One cannot look upon them and not smile in absolute delight.

Bloodroot, often still wrapped in their winter coats, are next to blossom.

Soon after, the yellow violets, who are eventually joined by their purple cousins. Robin Wall Kimmerer wonders why the world is so beautiful when she sees goldenrod and asters together. I think the same of the yellow and purple violets. If one is lucky, one can find the mostly hidden chameleon Jack-in-the-Pulpit beside the violets as well.

Another rare treat – Dutchman’s breeches. I’d been wanting to find them ever since my mother bought a sweet little book by Ellen Fenlon, Signs of the Fairies, with close-up photos of flowers and fern fronds, each captioned with how they were signs of fairies. The caption for Dutchman’s breeches was “Look!” said Stephen. “Pants on a clothesline.” Finally, a few years ago I excitedly discovered them on my favorite stretch of wildflower viewing on the Superior Hiking Trail.

I was blessed on my birthday this year to come upon an entire grove of serviceberry bushes. Though I had walked right by many every spring, I had never heard of them until recently when I came across a piece by Robin Wall Kimmerer, in of all things, Emergence Magazine, called “The Service Berry.” “The tree is beloved for its fruits, for medicinal use, and for the early froth of flowers that whiten woodland edges at the first hint of spring,” she writes. Encircled in that white ‘froth,” my encounter with them was magical. It seemed that the fairies had come ahead of me and decorated the woods for my birthday. I was enchanted. Kimmerer goes on in her piece to talk of how service berries inspire gratitude, and indeed they did in me, for my response was to say the Potawatomi Prayer of Thanksgiving – “the words that come before all else.” The Potawatomi name for service berries is Bozakmin. In Anishinaabemowen, to which Potawatomi is related, min or mino means “good,” and while this applies to the berries that will ripen this summer, the flowers that morning brought goodness to my day.

Now that it has begun to warm up, it seems new flowers emerge every day. Wild strawberries, bluebells, clintonia, wood anemones, wintercress, dame’s violet, blue vetch, buttercups, baneberry, and dandelions and forget-me-nots galore.

In June, great arrays of trillium adorn the forest floor, while their shyer cousins – the nodding trilliums – invite us to look more closely.

Pink and yellow ladyslippers will soon follow.

Yesterday, I was delighted to discover bunchberry blooming, my favorite probably because it bears the flower of my favorite trees, dogwoods.

The flowering bushes are preparing their feasts for birds – with the floral beginnings of black currants, chokecherries, honeysuckle, and red twig dogwood. They are all a feast for the eyes.

Today on a different trail, new surprises – Canada mayflower -- also known as false lily of the valley, orange and yellow hawkweed, columbine, and glorious blue and pink lupine.

Finding the right essay title can sometimes be a challenge, but this -- “Emergence” -- presented itself as an inspiration from the flowers long before I ever began writing. As I explored the word “emergence,” I discovered that both philosophers and physicists use the term to discuss the nature of causation and formation of things ranging from snowflakes to termite colonies to the murmurations of starlings to galaxies in the universe. I intended nothing so grandiose, or maybe more so, since for me it represents the rising of the life force itself – all that wants so much to come into being, to blossom. As a gardener, in the past several weeks I’ve observed this in the flowers and vegetable seeds I’ve planted. It is always such a thrill to see the first tender shoots come up through the dirt in search of light, of growth. Perhaps nothing captures this so much as the beans that are just now beginning to emerge from the soil, bending and straining, eager for life.

All of us keen for life do this – from our first emergence from the womb to our eagerness to learn to talk and walk and make music and dance, to venturing from the safety and security of family to the wider world of friends and school and play, to discovering our unique gifts and being in the world. It has been a great gladness in my life to witness my students as they emerged from shells of insecurities to confidence, from repressive ideologies to freeing new perspectives and self-recognition, from confusion to clarity, from unknowing to a grounded sense of self. Or perhaps I’m seeing myself in them, for that was my own journey.

As I look for the significance in what is catching my attention at this moment, I wonder what is emerging in myself. What new thoughts, perspectives, possibilities? What longs to come to light? This blog began by honoring the long-held desire in me to write essays -- freed from requirements of academia to write scholarly, documented books and articles to let my thoughts and ponderings meander on the page in something more formal than a journal entry but less rigid than an article or book chapter. Actually, each post reflects something emerging in me, some question that begs exploring, some idea that seeks expression, some sorrow or great joy or simple delight that longs to be shared. I’m grateful to all who take the time to read, and especially to those who send me their reflections in response. And so I leave you with the question, what is emerging in you?

Sources

Fenlon, Ellen. 1962. Signs of the Fairies. Akron, Ohio: The Sallfield Publishing Company.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. 2013. Braiding Sweetgrass. Minneapolis: Milkweed Press.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “The Service Berry.” Emergence Magazine. October 26, 2022.