I first saw it when looking at their faces while showing The Burning Times in class -- the blank stares, the pained expressions, the tears, the looking away. The scenes and sounds of women tortured and burned alive touched something deep and ancient in my students. Here it was -- the historical and inter- and transgenerational trauma of women.[i] The lasting impact of historical trauma is experienced by subsequent generations for hundreds of years, manifesting in such things as depression, PTSD, self-destructive behaviors, anger, violence, suicide, and more. As Native LGBTQ activist and writer Chris Stark so eloquently put it: “The experiences of our grandparents and great-grandparents are written into the library of our bodies . . . .My ancestors’ loss and screams are written in me – their pain and murder and rape merged with my own as a child. . . We carry them through time. We remember.”

It is so important that the historical trauma of Native, African American, and Jewish peoples is finally being acknowledged and addressed. More recently attention has been given to the historical trauma of Japanese Americans and other people of color, LGBTQ, immigrant, and impoverished populations as well. However, rarely are women as a group considered a targeted population, despite the ongoing trauma of living under patriarchy, the vast amounts of intimate partner violence and sexual assault, and the hundreds of years of the European witch burnings, dubbed by Andrea Dworkin “gynocide,” and its impact on indigenous women as Europeans colonized the globe.

During this time of the Celtic and Wiccan holiday of Samhain, the Christian Halloween, All Saint’s Day and All Soul’s Day, and the Mexican Día de los Muertos, it seems fitting to reflect on the historical trauma of descendants of “the burning times” – the hundreds of years from the 13th to the 18th centuries in which vast numbers of the peasant populations of northern Europe were accused of witchcraft, imprisoned, tortured, and burned alive. The estimates of the numbers of those killed varies from sixty thousand to nine million, but that about 85% of these were women is undisputed. “Were there two million or nine million witches burned?” asks Susan Griffin. “Whatever the number, we must imagine a conflagration, a mass terror, the constant odor of burning flesh, whole villages massacred, children whipped or thrown on the flames with their mothers” (Pornography, 80).

Poor women, wise women, healers, widows, spinsters – women living outside of patriarchal authority – were most vulnerable to charges of witchcraft. “Whilst not all women were the target of accusations,” Enya Holland pointed out, “it can be argued that ‘anomalous’ women were.” And it can be said, as Mary Daly did, that “the torture and burning of women as witches became normal and indeed normative in ‘Renaissance’ Europe” (201).

Why women? Historian Irving Smith believed it was because more women than men survived the plague, and the women healers and wise women were a threat to authorities, the Church, and the male medical profession. In her Dreaming the Dark, Starhawk provides a thoughtful discussion of the possible reasons, including the expropriation of the knowledge of the midwives and healers by the rising medical profession, but also what she called “the war against the consciousness of immanence, which was embodied in women, sexuality, and magic” (189). An aspect of this latter, and the one that I and others believe factored most heavily, was due to the Church’s association of women with the devil. That the Church considered women to be in league with the devil dated back to Tertullian in the 2nd Century CE who wrote of women, "You are the gateway of the devil; . . . Woman, you are the gate to hell."[ii] But it was with the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum by two Jesuit priests in 1486 that the association of women with witchcraft reached unparalleled levels. “All wickedness is but little to the wickedness of a woman. . . she is more carnal than a man, as is clear from her many carnal abominations. . . . All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women insatiable. For the sake of fulfilling their lusts they consort even with devils.. . . “

It became widely believed that “witches copulated with the devil, rendered men impotent. . . devoured newborn babies, poisoned livestock, . . . ” (Eherenreich & English, 35) As midwives and healers, they also engaged in acts, once considered important aspects of the healing professions, but at that time rendered criminal – contraception, abortion, and delivering babies without pain. And so it was easy to make women, especially women living outside male authority, scapegoats for the Black Plague and the poverty of peasant populations forced off their lands.

As Susan Griffin recognized, “. . . these deaths were only the climax of a series of events. For the witches were arrested first, and then put on trial, they were bound up and tortured and told to give evidence against themselves. . . .” In order extort confessions, the accused were “. . . hung upside down, beaten with whips and mallets, their fingernails were pulled out, they were put on a rack which violently stretched the body, a tortillon squeezed the ‘tender parts,’ . . . “ (Pornography, 80.) Torturers applied thumb screws to the victims’ fingers and toes, and shin screws pressed to the point that their shins would splinter into pieces. If the accused did not confess with the first level of torture, a second would be applied, and if not then, then the torturers employed the third degree in which all would confess.

That the torture was so sexual in nature must be stressed. While imprisoned, the accused would be stripped and most likely raped by the torturer’s assistants.[iii] They would be forced to face the priests, jailers, judges, torturers, and executioners -- all of whom were men -- naked.[iv] Their bodies were routinely searched for the “devil’s mark.” Torturers applied hot fat and tongs to the accused’s eyes, armpits, breasts, and vaginas.[v] Mary Daly asserted that, “a witch was forced to relieve her torture by confessing that she acted out the sexual fantasies of her male judges as they described these to her,” presuming that they “ . . . achieved erotic gratification from her torture, from the sight of her being stripped and gang raped, . . . and from her spiritual and physical slow death” (214).

How could this trauma not be felt and passed on for generations of women to come? As Resmaa Menakem notes, for centuries white bodied people passed this trauma on to other white bodied people, before inflicting it on indigenous and enslaved bodies in the Americas. The historical trauma of Europeans has spread throughout the globe as Europeans colonized much of the rest of the world, bringing their trauma and tactics with them. Menakem, however, lacks a gendered analysis, failing to note that certain sexualized brutality was specific to women. The same tactics of sexualized violence and torture of women accused of witchcraft would be inflicted on Native and enslaved women in North America, as they would be on Jewish women during the Holocaust and colonized populations of indigenous women around the globe.[vi]

The lasting impact of this historical trauma continues today in the silence, passivity, and internalized oppression of women, for somewhere ancient in our bodies we carry a fear that to speak out, to be visible, to claim space in the world is to risk imprisonment, torture, and death. The trauma continues as well as in ongoing tactics of sexual terrorism used to frighten, dominate, control, and silence. It lives on in pornography that mirrors the witch trial tortures, in sexual and domestic violence, in sex trafficking, and in ongoing efforts to prevent women’s sexual and reproductive autonomy through bans on contraception and abortion and threats to imprison and murder those who would assist a woman in these.

The effects of the burning times are still with us. I can feel this in my own body. As Starhawk put it so vividly, “the smoke of the burned witches still hangs in our nostrils, . . . remind[ing] us to see ourselves as separated. . . in competition with each other, alienated, powerless and alone” (219). However, she continues, “the struggle also continues.” That struggle is the impulse toward wholeness, healing. That journey toward healing begins with remembering and acknowledging past harms, so that we may better understand who we are and the ways these continue to live in our bodies, psyches, and culture in order to address them.

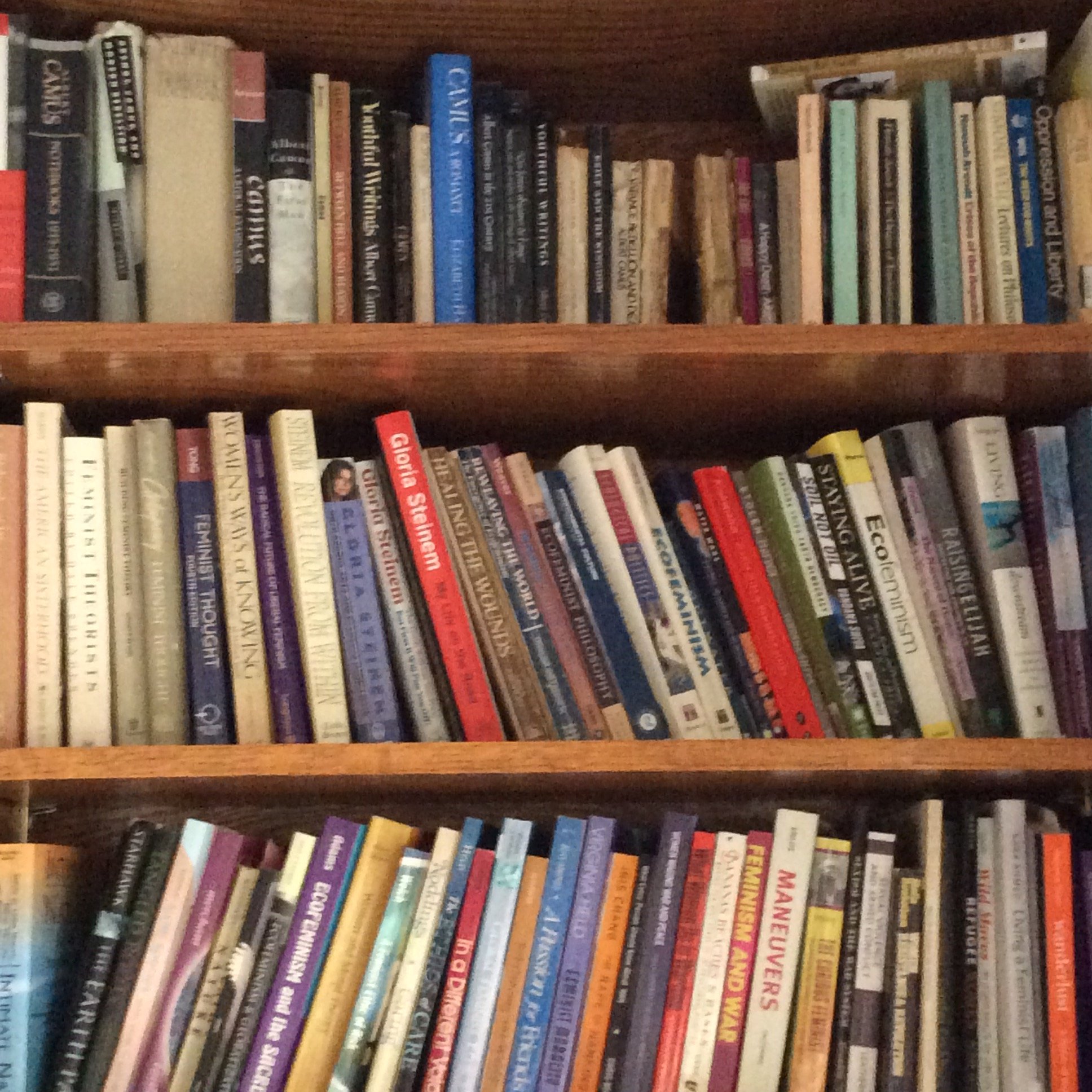

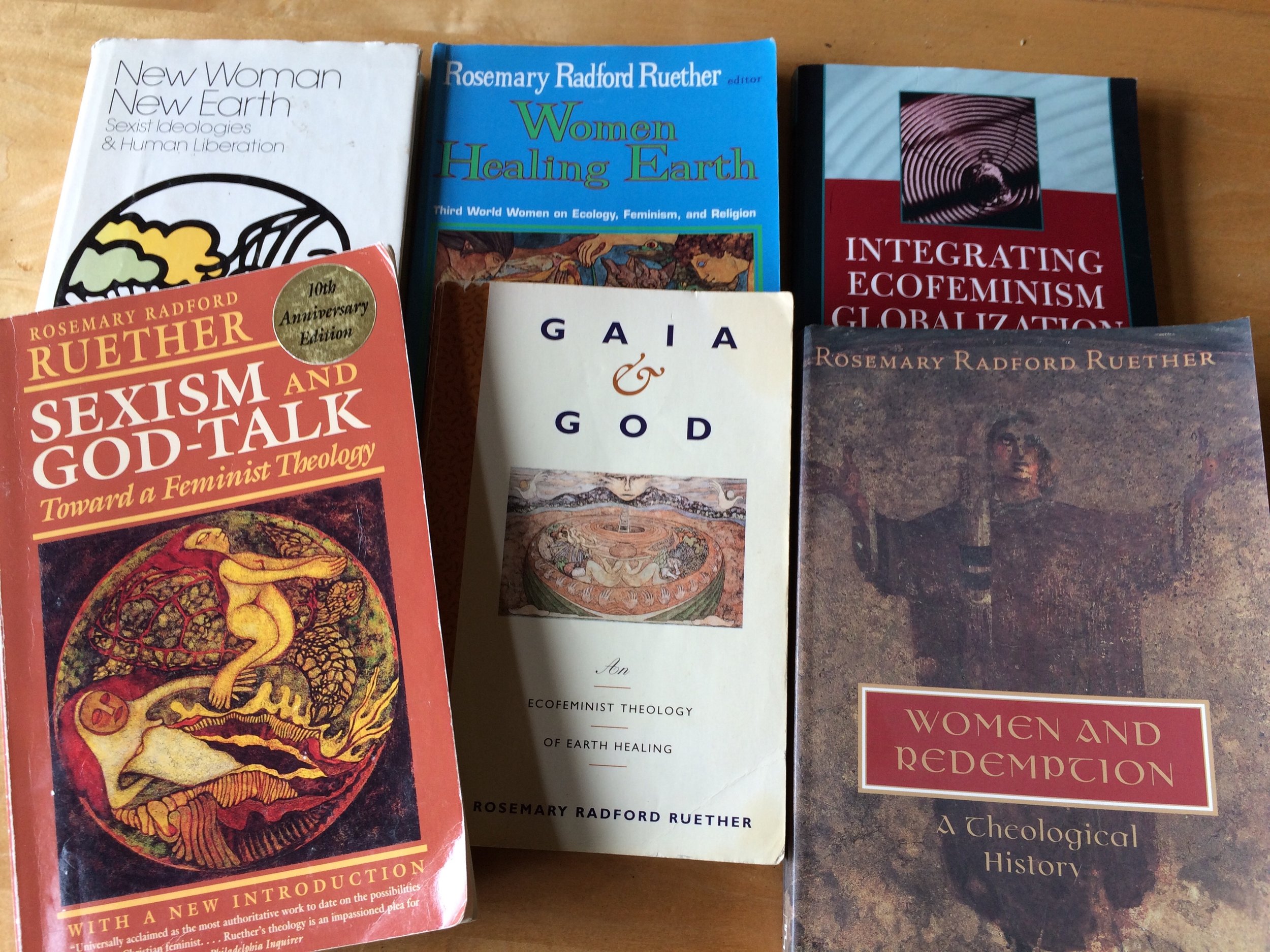

In South American indigenous cultures, trauma is recognized as susto, or “soul wound,” and it is on that level that healing needs to happen.[vii] To quote Shirley Turcotte, “Healing from trauma is a spiritual matter, a relationship matter, and there are places in recovery that require a precious spiritual response.”[vii]i The women’s spirituality movement that burgeoned in the 1970s and 1980s continues to be one such precious response The work of Starhawk and others to reclaim the word “witch” and to revive and reimagine a tradition of valuing immanence, the sacredness of the earth, and the ability to change the world for the good has been invaluable in this.[ix] In their efforts to reform and re-envision the predominant male-centered world religions, feminist theologians have also made steps toward healing the aspects of those traditions that have been so damaging. In their revival of ancient goddess worship, Carol Christ and others have worked to restore the energy and sacredness of the feminine divine to a broken world so in need of this.

As we learn more about the ways trauma lives in our bodies and our very cells, other paths of healing are opened, and we are learning how to metabolize and discharge ancient traumas.[x] A few years ago, Tina Olson, then director of Mending the Sacred Hoop,[xi] told me that as they were seeing patterns stemming from past abuses repeating in the next generations, they were shifting the focus of their work from the criminal justice system to healing. They were providing trauma-informed care that engaged women in healing at their own pace in a way that is more traditional, and takes into account their physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual healing. At that time, I had little idea of what that entailed until I had the privilege, through Mending the Sacred Hoop, to be trained to offer such healing practices through Indigenous Focusing Oriented Trauma (IFOT) therapy. It was an incredible honor to learn from indigenous elders from British Columbia, as well as from those in my training cohort. Even though I had already trained in Somatic Experiencing® trauma therapy, this decolonized approach completely altered my worldview and sense of the space-time continuum. I learned that the “felt sense” in each of us “is our teacher and our natural way to spiritually connect with our ancestors and to connect with all of life and land” (Turcotte & Schiffer, 61). The indigenous approach recognizes all our relations, and that the medicine may reveal itself in a dragonfly, a stone, in cedar, or the waters of Gichi Gami. I distinctly remember Shirley Turcotte (the founder of IFOT) saying that first day, “All time is now.” It was only through immersion in the practices that I came to understand that the past, present, and future all exist simultaneously, so that in healing in the present, we are also healing the trauma of our ancestors, and that of generations to come. Similarly, in the course of the practices, often healing would come through the assistance and wisdom of an ancestor. As Turcotte said, healing from intergenerational trauma requires moving between dimensions with kindness and grace. I know this healing to be possible.

At this time of year, as we honor and restore our relations with our ancestors, with each other, and the earth, I am reminded of the words of Susan Griffin, “The earth holds a vast wisdom and a capacity to heal that we are only beginning to comprehend. We are made from this earth. This is my hope” (Made from this Earth, 20).